Where do wandering gliders migrate?

Wandering Gliders are highly migratory and posses impressive dispersal powers. They spend much of their time wandering long distances searching for recently filled rain pools where they breed. In North America, they are resident in the southern United States, but adults will often migrate north in the spring to breed.

How do you identify a wandering glider?

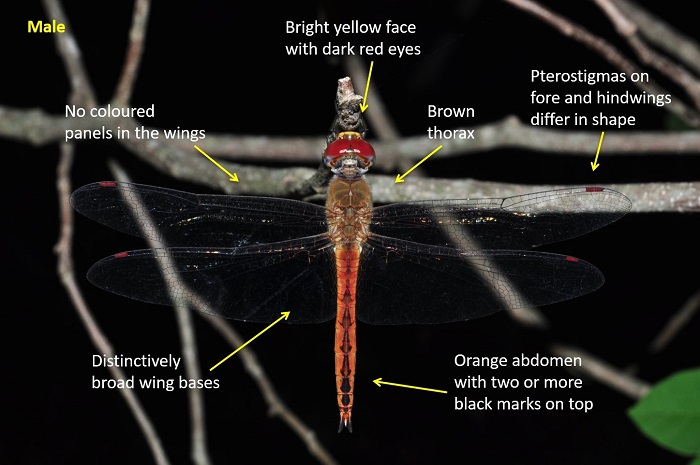

Identification. Length reaches 53mm; Wingspan up to 90mm. Pantala flavescens is easily recognised by its distinctive, tapered shape, yellowish to orange-red colouration and long, broad-based wings. Most resembles Tramea basilaris (Keyhole Glider) and Tramea limbata (Ferruginous Glider).

Do wandering gliders fly tirelessly?

They fly tirelessly with typical wandering flight for hours without making any perch. Their flight speed is up to 5 m/s. Especially in the autumn, the wandering glider flies in large swarms, using thermals to advantage.

Wind is a good friend to the Wandering Glider. This dragonfly uses air currents to do most of the aerial work for it and can stay in the air for hours before resting. When they do land, one can see their markings and coloring for a clear identification. The abdomen is yellow, though in males it may be more orange-red. Fine black lines cross the abdomen and a black line down the dorsal side (‘spine’) swells a bit in each segment. Clear wings each have one yellow-brown cell at the upper edge, resembling a tiny fragment of stained glass. Adults can fly in swarms with other adults, and even among other dragonfly species, as they feed on flying insects.

Mating is done while in flight. Females lay fertilized eggs in ponds, temporary puddles left by rain (hence the alternative name of Rainpool Glider), and swimming pools. Reflective surfaces like car hoods and wet asphalt are mistaken for water and females have been seen trying to lay eggs on them. Naiads (juveniles) spend this early life stage in the water feeding on aquatic insects and plankton. They crawl onto land when ready to molt into winged adults. They can survive dry spells on land, further attesting to this species’ resilience.

General Description

We do not yet have descriptive information on this species. Please try the buttons above to search for information from other sources.

Range Comments

The Wandering Glider is distributed throughout most of the southern half of North America south to the tropics. They also commonly occur in the tropics of the eastern hemisphere as well as many oceanic islands and tropical regions. Interestingly, the only continent they are absent from is Europe (Dunkle 2000, Paulson 2009).

Migration

Wandering Gliders are highly migratory and posses impressive dispersal powers. They spend much of their time wandering long distances searching for recently filled rain pools where they breed. In North America, they are resident in the southern United States, but adults will often migrate north in the spring to breed. These young develop and emerge, eventually migrating south again in the fall (Dunkle 2000, Nikula et al. 2002, Paulson 2009).

Habitat

The habitat of the Wandering Glider includes a wide variety of temporary pools, ponds, puddles, other wetlands, as well as ditches, artificial wetlands, garden ponds and even swimming pools. Fishless environments are the usual (Dunkle 2000, Nikula et al. 2002, Paulson 2009).

The favoured breeding habitat is at seasonal pools, pans and dams which it rapidly colonises after rain. Liable to turn up almost anywhere after a down pour. Often found in large numbers hawking over lawns, sports fields and any other open spaces.

They fly from one nation to another during the annual passage in autumn, the Indian Ocean a canvas of blue below, their biplanar wings attuned to thermal updrafts, the propulsion of the trade winds, the cycling of the monsoons.

In half a century I have never perceived the color blue as these tiny flyers must experience it in this moment. Even if I were to ride the Somali Jet beside them, my arms outstretched to mirror the translucent lift of their wings as we glide 1,000 meters over the peaks and troughs of the ocean, sunlight burnishing the horizon at dawn in peach and tangerine behind us—the layered depths of the color blue in the waters below would stun the language from my lips, and yet those waters would lack the thrumming electricity of it all, where striations of blue flare in wavelengths of light I am simply incapable of seeing. That blueness. It exists within this world, though I will never live to see it. The compound eyes of the dragonfly have 30,000 facets, and while I live with the wild combinations of three cones in the orbit of the eye, mixing reds and greens and blues, I cannot fully comprehend the pigments and hues possible through the combination of 11, or 12 separate cones—as the visual spectrum within the dragonfly represents a world that might blind me with its beauty.

And these tiny flyers, alone or in great numbers, cross the ocean when the season calls them, from Kerala and Tamil Nadu, and from waterholes and lakes further north, the underwater naiads transforming into winged beings that emerge from the tenuous surface of the wetlands in Chennai, or from the channeled lowlands in the Kaveri River delta. Dragonflies. They rise and take flight. Cattle bellow with their god-like voices, urging them on toward the theater of clouds. Feathered hunters pluck some of them from the empty air to dismember them and eat them before landing in the leafy shade of giant banyans—trees that walk their slow way through the marshlands, century by century. And yet the wandering gliders fly on, from the Kingdom of Animalia, the Phylum Arthropoda, from the Insecta Class and the Order of Odonata in the Infraorder of Anisoptera, from the Family of Libellulidae and the Genus of Pantala, they fly by the millions over the green earth and over the blue ocean, Pantala flavescens—the wandering glider, the yellow dragonfly with delicate wings.

They are so driven that sometimes they fly against the wind, buffeted by it, persevering, on azimuth and true to an idea so deep within the body only the dead that came before them know of the water they might alight upon in a land they have never seen. They fly from India to the Maldives, and then on over the ocean to Nairobi, Kampala, Dar es Salaam. The sun rises to warm their slender forms. Day blurring into night. Dawn. Dusk. The blood orange of a moon rising into the pale blue of evening. A field of stars trembling in the waters below. And as they fly, the metallic bodies of flying fish glint in the brief moment they thread the midnight waters with silver needles of light. The dragonflies chart the salty wakes of massive container ships bound for the Red Sea, or the lateen sails of dhows plying the trade winds as they have for generations.

They eat micro-insects and airborne plankton en route, and they are eaten in turn by those that can catch them. They are sustained aloft by winds that resonate with a high, thin voice some might consider the voice of the Earth itself, calling out into the darkness of space as it spins among the planets churning through the dust of stars. And when the winds die down and the air is stilled and the dragonflies find themselves far out to sea, the vast blue waters rise and fall in a tandem conversation with the inscrutable blue sky. This is when they must fly on their own; and their wings, so light and fine, veined into a mosaic of glassy panes, must shape the invisible until it hums once more, each flyer singing themselves forward, and deeper, into a meditation on blue.

Interesting facts about dragonflies:

Dragonflies are some of the world’s best fliers. Pantala flavescens, also known as the Wandering Glider or Globe Skimmer take part in a multigenerational migration every year. They make an 18,000 km (11,200 miles) journey, in which individual dragonflies fly around 6,000 km (3,730 miles). As a result, they might be some of the most widespread dragonflies, with populations on every continent except for Antarctica. The Wandering Glider is about 4.5 cm long, with wingspans of 8 cm. How do insects so small fly so far? Dragonfly wings and flight dynamics are a wonder and a great biomechanical inspiration.

Several characteristics of dragonfly wings enable efficient flight. One of these is how they beat their wings. Dragonflies have a pair of forewings and a pair of hindwings and can modify the phase those wings beat at. The wings can beat together (in-phase) or out-of-phase, where a pair of wings point up and a pair of wings point down. Studies have shown that in-phase flapping creates lots of force, which is best for takeoff or quick, demanding manoeuvres. Out-of-phase flapping is for steady flight and hovering. This mechanism has been termed ‘counter-flapping’. When the forewings flap, they create a leading-edge vortex that the hindwing anticipates and catches. This means that the hindwing captures the energy that is ‘wasted’ by the forewing, decreasing the energy the dragonfly uses and increasing its lift.